| General

Winfield SCOTT came to Illinois in 1832

with a force of one thousand regulars to take from the faltering hands

of the state militia the task of winning the Black Hawk War and

concluding

a peace. Part of his force was stricken with cholera when they arrived

in Chicago. Others were stricken when they arrived in Rock Island where

peace negotiations were then in progress.

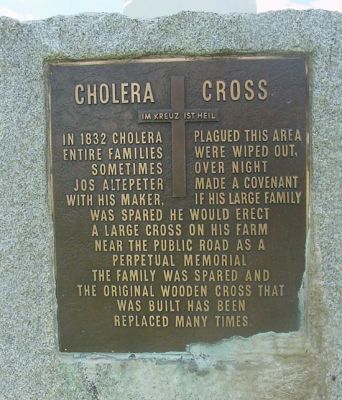

The disease spread throughout the countryside, carried by roving Indians and army stragglers. Because of a devastating outbreak at Rock Island, negotiations were moved to Jefferson Barracks at St. Louis. From there, the cholera spread to Southern Illinois and started the terrible cholera epidemic years that plagued Southern Illinois from 1832 onward. Newspapers of that time tell the most amazing stories. People died like flies, both in the cities, and in the rural areas. One story tells that in Belleville, about 30 miles away, the death toll was 10 per day. St. Louis, about 40 miles away, had 601 deaths in a single week. An entire farm family of 10 was wiped out overnight in Lebanon, about 20 miles away. Although Germantown, Breese and Carlyle were the three Clinton County towns with the most staggering death tolls, all areas of the County suffered. The epidemic was called the Black Plague and raced through the whole country like an uncontrolled prairie fire. During the day, a man would apparently be in robust health; by night he was burning up with fever; by dawn he had died a miserable death. No one recovered. Doctors were scarce, and what few there were in the area knew nothing about the disease or how to stop the epidemic. People grew panic-stricken. Village streets were sprayed with lime. Fires of coal, tar and sulphus were kept burning at street corners. Citizens were told to use chloride of lime, boiling vinegar, tar and burning coffee in their homes as preventatives. Of course nothing worked. The dead were carried to cemeteries and buried at night. It was a time of great suffering and overpowering anxiety. A few years earlier, the same disease had swept over Europe and ravaged whole populations and killed millions of people. It was during this crucial time that Joe ALTEPETER, a farmer living north of Germantown, made a sacred pledge to God. His family thus far had escaped the plague. But it was on all sides. They went to bed, terrified, and awoke in the morning, still terrified. Each moment they wondered who would be the next victim. Altepeter, a religious man, asked his Lord to spare his family. He promised that if they were spared, he would make a perpetual memorial in the form of a large cross, erect it on his farm, so all could see the evidence of his faith. And, strangely, the Altepeter family was spared! This is HISTORY, not fiction. Joe Altepeter went to the woodlot and hewed out timbers for a large cross. He mounted it near the roadway, in front of his home, facing the rising sun when it came over the prairie from the east. That was built in 1850. On it, in German, he inscribed the words "Im Kreutz ist Heil" "In the Cross is Salvation" The original cross was replaced when it decayed. People are uncertain exactly how many times the cross has been replaced. The current cross is made of concrete. When Joe Altepeter died, the farm passed to his son Henry Altepeter, who in turn passed the farm to his son Bernard Altepeter. In 1930, Bernard Altepeter passed the land to Gerhard TIMMERMAN, a brother-in-law. Gerhard Timmerman passed it on to his son Joseph Timmerman, who in turn has passed it on to his son. There had been stories that the deed required all purchasers of the 160-acre homestead to maintain the shrine in good repair. Joe Timmerman said: "There is no such requirement. The cross was placed there by a man who had faith in God. It remains there for the self-same reason." Today’s cross can be seen near the road that runs from Breese to Germantown. It is in the same location as the original cross, about a mile south of Breese. The huge cross, in solitary beauty, perhaps 25 foot high, is just off the lane that leads to a well-kept dairy farm. It still stands today, about 150 years later, in mute testimony as a shining symbol of a man’s faith in God in a time of great stress. A brass plaque is at the base of the cross stating this. Cholera is an acute infection of the intestine, resulting in severe watery diarrhea and often accompanied by vomiting, which results in dehydration of the body often within a few hours. In 1886, doctors discovered that cholera is caused by contaminated water or food, especially when involved with human waste, or by coming into contact with an infected person. This discovery basically led to an end of the cholera epidemics throughout the world. Today, cholera appears only when an act of nature, such as earthquake or great migrations of people, such as during wartime, lead to situations where public hygiene is lacking. Today a body can be rehydrated with mineral salts and sugars. |

Photos courtesy of Paul Lindauer |

Compiled and Transcribed by Dorothy Falk